Zeenat Muhammad’s days as a neuroscience major at the University of Illinois-Chicago (UIC) are busy. Now a junior, she’s double minoring in chemistry and nutrition, secretary of the Women’s Health Initiative and vice president of Blood Buds, a student-led organization working to fight period poverty.

“A lot of people ask ‘how do you juggle it?’ I don’t even look at this as an activity, it’s just kind of natural,” she said. “I think passion takes you far.”

UIC began stocking period products in some school restrooms during her freshman year but according to Muhammad, the machines were not consistently stocked. Last semester, Blood Buds focused on contacting student advisors from the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences (LAS), UIC’s largest college, to prioritize making sure the dispensers were filled.

“This semester, fortunately, not only have we seen an increase in the number of dispensers of pads and tampons, they’re completely stocked up… And we pushed for the school to put a contact number on the machine so that if it’s out, somebody could text message and let them know. So there’s never really a point of negligence,” she said.

The law requires these products to be there. In 2021, Gov. Pritzker signed HB 641, requiring all public universities and community colleges in Illinois to provide free period products in restrooms. While a growing number of states have enforced laws that require schools to provide period products to students, Illinois, California, Oregon and Washington, D.C. are the only that have policies specific to higher education institutions, according to Inside Higher Ed.

UIC currently houses 34 Aunt Flow dispensers across their East and West campuses. The Richard J. Daley Library holds the most, with six dispensers spread throughout three floors. Most of the academic buildings have one or two.

“A lot of people who are facing financial crisis now don’t have to worry about access to period products, at least not on campus,” said Muhammad.

Why do college students need free products?

College students are notoriously broke and higher education is expensive.

Federal data released this year by the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES) supports the notion that many students are struggling to get by. According to the data, 4 million college students experience food insecurity, and 8% of undergrad students are homeless.

The average cost of college tuition, including books, supplies and living expenses averages out to $36,436 in the U.S., according to Education Data Initiative. Cost of tuition is $9,349 at the average public 4-year institution, but is 23% higher in Illinois. Attending a private university in the state is 7% higher than the national average.

These costs are making students weigh out their needs. In September, intimate health brand Intimina revealed that their study of five universities showed that almost 19% of female college students said they’ve felt forced to decide between buying period products or meeting other expenses such as paying bills or buying food. A similar study by BMC Health in 2021 found that 14% of women attending college experienced period poverty in the past year, and 10% reported experiencing it every month.

The American Medical Association has urged the IRS to consider period products a medical necessity, to remove barriers to accessing products in correctional facilities and prevent these goods from being taxed. The National Organization for Women estimated that menstruators spend about $20 per cycle, adding up to $200 to $300 a year, but Yahoo Finance reports that the prices of pads and tampons increased up to 10% last year.

This generation of teens and young adults care about menstrual health. The latest State of the Period survey shows that 89% said they think that menstrual products are just as important as toilet paper or soap in public restrooms.

“We don’t choose this… Free products are important for folks because for students, I think that’s a particular place in our lives where we’re trying to learn, we’re trying to focus in school and having to worry about that while on campus, while in a learning environment, and even off campus is something that is so basic and so easy to solve,” Abigail Suleman, co-founder of Blood Buds, said at IL Latino News and WBEZ’s Community Conversation earlier this year.

Students have motivated universities in IL to implement free programs

Though private schools are exempt from this policy, pressure from students has influenced universities to adopt similar measures on their own campuses.

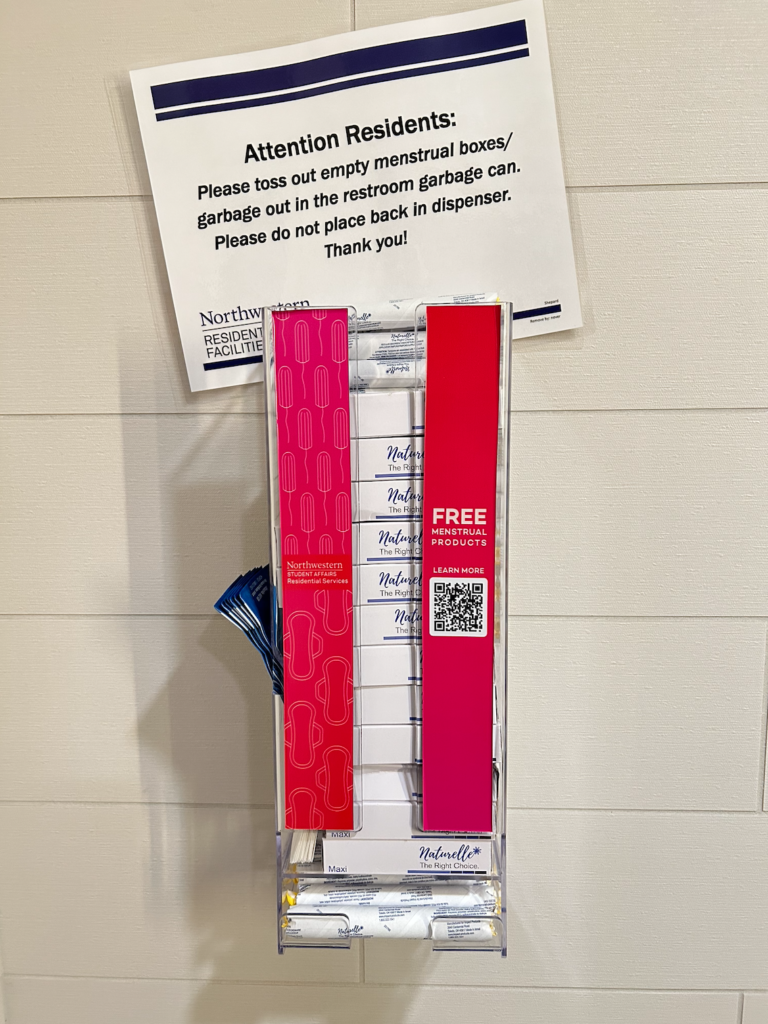

In 2022, Menstrual Equity Activists (MEA) at Northwestern University created a survey to understand the need for free menstrual products at Northwestern, generating 662 responses from students. 99% of respondents said it would be helpful to have menstrual products in residence halls/residential colleges, and 100% of menstruators said that they would use free menstrual products in dorms.

Residential Services used this data, installed dispensers and now provides period products across campus. Students can even provide feedback on this online form to report dispensers that need to be restocked.

“Unfortunately, we’re still working on getting every bathroom on campus stocked with products but any building you go to, any dorm that you’re living in, has them in at least one of the bathrooms,” said Lili Pope, co-president of MEA.

At Loyola University, Students for Reproductive Justice (SRJ) started leaving free period products in plastic containers by the sink in both Lake Shore and Water Tower campus restrooms themselves in 2017. According to Ella Hansen, an SRJ organizer, the university agreed to take over responsibility of the Menstrual Equity Project in Fall 2019, but once the COVID-19 pandemic hit there wasn’t a need to follow up on the project with no students on campus.

“Once we all returned in person, they had fully taken on the project, but there were a lot of issues with it,” said Hansen, citing inconsistent stocking and recurring transphobic instances.

A 2019 video shared on Snapchat showed a man tossing out a box of period products meant for transgender men and gender nonconforming people using the men’s restroom. According to the Chicago Tribune, it earned over 1 million views.

“We’ve been working with them to get dispensers permanently affixed to the walls to prevent that kind of stuff. And just to make it more concrete, you know, that they’re going to be there and they’re going to be free for a while,” said Hansen.

SRJ’s goal has been to consistently provide free period products in the restrooms of all genders, in all buildings at Loyola – but it hasn’t happened. The organization says there has been continued conversation with Loyola Facilities, with renewed hope for thorough implementation of the Menstrual Equity Program as new administration has taken over the project at the university’s end.

Blood Buds, MEA and SRJ are all very vocal about the importance of making these products accessible beyond women’s restrooms.

“Most of the bathrooms with the products in the dorms are the gender neutral ones on the first floor. We were very grateful that residential services tried to be as inclusive as possible,” said Pope. “Nowadays there’s like way more people who don’t necessarily identify as a woman who can access the product so that was appreciated.”

According to NPR, there is currently no list recording how many colleges and universities in the U.S. provide period products to their students for free.

_____________________________________________________________________

Publisher’s note: This reporting is supported by a fellowship with the Journalism & Women Symposium (JAWS), sponsored by The Commonwealth Fund, in partnership with Reckon News.