“You make me feel at home,” read a little post-it note, placed right at the center of the whiteboard in my classroom. I knew that for Elena, one of the English language learners in my 3rd grade classroom, home meant more than a roof over her head; it transcended borders between the United States and Mexico. Spanish was the only language Elena spoke at home and every word reminded her of love, comfort, and connection. Home was a place for authenticity where Elena could be herself and vulnerable.

Just last week, Elena’s general education teacher reached out to me concerned that she had not spoken many words. But in my small group setting, that same week, I heard her voice soar during a “If you only knew” portrait activity I had planned. Elena had drawn a beautiful picture that revealed details about her world. She sketched the U.S and Mexican flag enveloping a sad face, echoing the silent struggle of being away from her family, culture, and language. Elena’s voice, once a murmur, echoed loudly allowing me to connect with the depths of her experiences.

Elena’s story mirrors a larger trend. In 2020, the United States had an English Learner population of nearly 5 million, constituting 10.3% of the total student body. In Illinois, 14.6% of students in our state have been identified as English language learners. With this continual demographic shift, all teachers are becoming language teachers by default. It is therefore our collective responsibility to recognize and honor the unique gifts that students like Elena bring to our educational communities.

Here are three ways I support Elena and other students like her in my classroom:

I get to know them deeply, beyond the traditional first day of school “All About Me” activities. I take the time to understand the linguistically diverse learners in my classroom in order to foster a genuine sense of belonging and connection. I learn to pronounce each student’s name, connect with their families to devise plans and goals together, and embrace their cultural and linguistic diversity. And I actively look for ways to draw each student out and make sure they feel seen, valued, and supported. For some, this might be writing. For others, like Elena, a portrait activity becomes an avenue for their unique narrative, offering a more tangible representation of who they are.

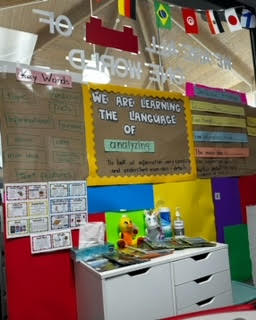

I teach them well. English language learners need more than just visual aids. Linguistic scaffolds are not only best practice, they ensure that students like Elena can equitably access the core curriculum and be active participants in their learning. In my school, we are lucky to have access to a rigorous literacy program and a focus on ensuring that it is aligned with the best practices of science of reading. However, to bridge the language gap, I need to be explicit in oracy instruction (listening and speaking). I am intentional about creating opportunities where students can purposefully practice academic language; sentence starters are used to structure discussions and support students in articulating complex ideas. For vocabulary development, I supply word banks and vocabulary journals with key terms to strengthen their command of content-specific language. In addition, I simplify explanations and pair abstract concepts with visuals. Much like an engineer planning, designing, and ensuring the structural integrity and functionality of a reliable bridge, I engage in educational engineering in which oracy serves as a foundational pillar. For instance, the sentence frames I devised for Elena gave her exposure to grammatical structures she is unfamiliar with in English, allowing her to convey coherent content-related ideas in both speaking and writing. This structured approach enables our linguistically diverse learners to navigate both content and language development.

I keep the bar high and challenge my students. Students who are still developing English language skills are often met with preconceived notions surrounding their academic capabilities which can create a rigor gap. But I know that language proficiency does not equal overall intelligence. Every day, I presume competence and reexamine my assumptions. I acknowledge and confront my biases. And, I practice culturally responsive teaching and draw from an asset-based perspective instead of a deficit one, recognizing that English learners bring a wealth of experiences and unique perspectives to my classroom. I know that my 3rd graders are capable of anything and can reach any mountain top. Right now, they are writing persuasive essays that support learning a second language as part of the curriculum, aiming to open the door for their peers to experience the joys and challenges of being language learners. In doing so, they hope people from different backgrounds can understand and appreciate each other’s cultures. Once these essays are complete, I will share them with our district and state superintendent.

Even with supports in place, it is essential that Elena and others like her have access to qualified teachers to guide them. We need to restructure teaching programs to ensure that new teachers entering the profession are well prepared to teach our English learners. And we must ensure that all teachers, even those with years of experience, have ongoing training to teach students like Elena.

Elena has made it into the honors program at school. She is now an academic mountaineer, reaching new heights in her educational journey. The post-it note Elena once wrote me later evolved into a full, well-written letter that closed with: “Thank you for believing in me, Mrs. Dominguez.”

Roseana Dominguez is a K-5 English language learners teacher at Ranch View Elementary in Naperville, Illinois. She is a 2023-2024 Teach Plus Illinois Policy Fellow.

Cover Photo by Pixabay

Publisher’s Note: The views, opinions, positions, or strategies expressed by the author are theirs alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views, opinions, or positions of Illinois Latino News.

If you have an idea for an Opinion-Editorial piece, please send your ideas to Info@LatinoNewsNetwork.com for consideration.