No one should have to choose between decent, safe, affordable housing and one that is insecure, unhealthy, or worse – be forced into homelessness.

Accessing suitable housing not only meets an individual’s social needs, but also bulldozes barriers to fair employment, education, and health care ensuring community strength and growth for the entire populous.

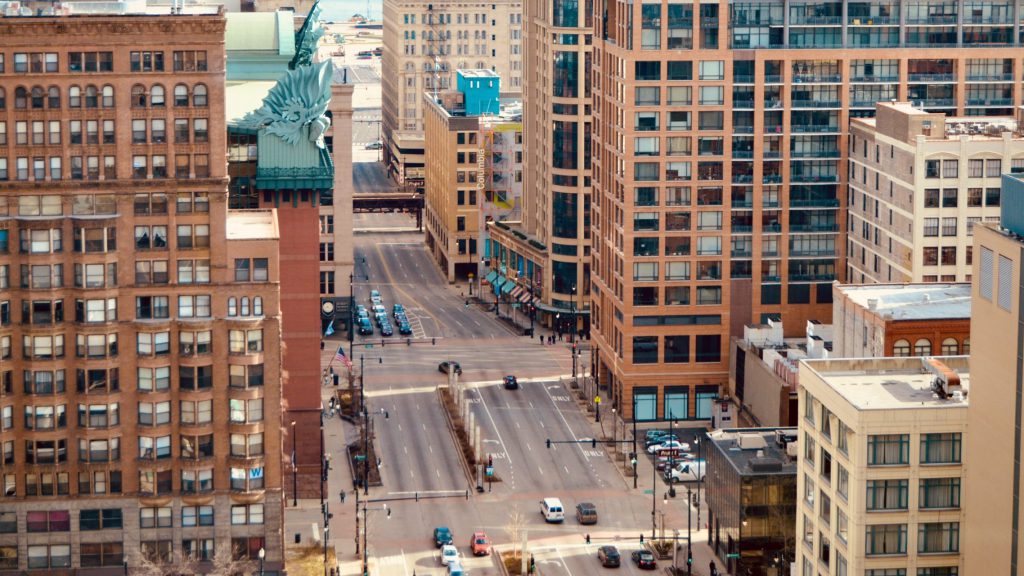

Over decades in the making, Chicago’s housing crisis has only been intensified during the COVID-19 pandemic with the increased threat of evictions, foreclosures, and bankruptcy.

Despite declines due to the pandemic, Chicago’s average rent is just under $2,000 and the median home sale price is $253,000, according to residential real estate platforms. Those listings vary considerably in North and South Side neighborhoods.

While data varies, after you factor in the cost of living expenses such as utilities and groceries, a renter needs to bring in a salary of around $95,000 a year and $85,000 a year for a homeowner. The problem is that the median annual income in the city is just over $52,000.

People of color are at a higher risk of housing insecurity due to Chicago’s history of racially targeted policies and widespread discrimination by the government and private sector.

Affordable housing reform initiatives have largely been focused on the Black community due to systemic segregation keeping them from attaining wealth and all the benefits that come with it.

It is important to include Hispanics-Latinos in the conversation as this growing group not only faces some of the same challenges of other marginalized communities but in some cases other limitations like language and immigration status.

Many of them are gentrified out of their neighborhoods like Pilsen, Little Village, and Humboldt Park – taking with them the diverse cultural identities that made those areas unique.

Finding an equitable place to live in Chicago shouldn’t be this difficult.

A History of Segregation

You wouldn’t think it to look at the make-up of Chicago’s neighborhoods, but the city’s population is more or less evenly split between Hispanic-Latino, Black, and white communities.

Most white people live on the North Side, most Black people live on the South Side, with a significant number living on the West Side, and Hispanic-Latinos have footholds in both with a concentration on the West Side.

A two-tier residential segregation strategy has kept Black and Brown communities from leaving neighborhoods historically suffering from neglect: evading investments in areas where people of color lived and restrictive covenants keeping middle-class neighborhoods white.

While the Housing Act of 1937 may have intended to provide quality homes to low-income and vulnerable people, it did more harm than good. Slums were replaced with public housing in inner cities cementing so-called minority neighborhoods.

In the late 1800s, redlining began to suppress people of color from receiving loans to buy homes in other neighborhoods by a real estate industry that believed it was their ethical duty to preserve racial homogeneity. The practice also denied these communities from renting buildings, apartments, and the means to improve their current homes.

Suburbanization and major road construction like the Dan Ryan Expressway marking a division between the predominantly white neighborhood of Bridgeport and the expanding “Black Belt” neighborhoods to the east further segregated communities.

Those types of discriminatory standards prevented people of color from accumulating wealth through homeownership.

While those practices are no longer legal, their effects linger today. The racial gap between Black, Brown and white populations across an array of quality-of-life indicators has been exacerbated during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Hispanics-Latinos, along with other communities of color, have been disproportionately harmed by the coronavirus due to social determinants of health beginning with where they live.

“The pandemic underscored what many of us already knew — that historic disinvestment has dire consequences for health, wealth, and opportunity,” said Luis Guitierrez, CEO of Latinos Progresando, in an interview with WBEZ. “We’ll need deep, multi-sector collaboration to build a renewed future, and this tool will be so important for nonprofits as they design programming and pursue funding, and for the private and public sectors as they determine where resources will be invested.”

The map Guitierrez mentions is The Mapping COVID-19 Recovery Project linking historic disinvestments in some Chicago neighborhoods with the pandemic’s impact on the residents who live there.

Solutions need to be culturally determined

The killing of George Floyd, and the unified grief and anger that reignited demands for justice not just in policing, but across several facets of American society, we have to ask ourselves – what are we going to do about it?

Chicago’s housing crisis is a secret to no one. Just like it is a well-known fact we live in a segregated city by design. The truth is, there are plenty of solutions, some that can be implemented right away and others that require more time. The problem is leadership with the vision and courage to get the job done.

Correcting systemic housing inequality will require mobilizing public and political will in designing policies inclusive of all communities.

In April, Mayor Lori Lightfoot released the Chicago Blueprint for Fair Housing, an initiative to mitigate and eliminate barriers. Among the eight goals for the next five years is to increase and preserve affordable, accessible housing options.

Now, that’s a good start considering housing and rent prices have accelerated faster than household income. Hispanics-Latinos spend almost half of their monthly income on housing costs. Extensive mortgage and rent relief are needed, and programs and services should be fully accessible and available in Spanish.

Most U.S. Hispanic-Latino households are multigenerational, pooling resources to make ends meet and stay out of poverty. However, affordable housing is seldom developed with those types of families in mind forcing many of them to live in overcrowded rental units not meeting their economic and cultural needs.

And when new developments are being built, it is all but exclusively in high-poverty areas keeping people of color from moving into more affluent white neighborhoods.

“We have to be honest that government has been complicit with the private sector for decades in segregating our communities and devaluing Black and Brown spaces,” said Marisa Novara, commissioner of Chicago’s Department of Housing.

The city says it will restructure the Low-Income Housing Tax Credit program to incentivize developers to build in highly-resourced areas, giving marginalized people more choices and mobility.

Still, once the affordable units go up, Hispanics-Latinos face other forms of discrimination. They are shown fewer units and called back less often. Hispanics-Latinos are also provided with less advantageous financing information, quoted higher fees, and more extensive application materials than their white counterparts, according to a report published by the Committee on U.S.-Latin American Relations (CUSLAR).

Surveys of Hispanic-Latino renters have found that information gaps about the homebuying and mortgage qualification processes have discouraged many from pursuing homeownership because their misunderstandings about the process lead them to believe that homeownership is unaffordable or too complicated and that banks are not to be trusted. Hispanic-Latino homeowners live in higher-cost markets, taking out debt with lower down payments in purchasing new homes.

A concern that Sylvia Puente, President, and CEO of the Latino Policy Forum shares citing WBEZ and City Bureau findings that Chase Bank had the most racially disparate lending record of all Chicago’s major lenders. Chase had given out more than $7 billion in home purchase lending between 2012 and 2018 — but just nearly 2% of that money went to Chicago’s Black and Brown neighborhoods.

“We (Latino Policy Forum) have not heard about the need for equitable investment in the Latino community to the degree that we would like (compared to the Black community) from banks and other investment initiatives”, says Puente.

Puente also cautions, “We will also need to pay close attention once the covid housing moratoriums are lifted. This will also adversely impact the Latino community for both renters and homeowners.”

That storm is looming not far in the distance. Housing advocacy groups like Unidos US suggest eliminating foreclosures and extending mortgage forbearance to help homeowners on the brink. The group also supports freezing evictions for tenants on all rental properties and providing tax credits for small landlords renting properties without a federally backed mortgage so they can weather the loss of income.

Even before the pandemic, Chicago was facing an accessible and affordable housing crisis fueled by racism that is now escalating because many more people are now experiencing housing insecurity for the first time.

Hispanics-Latinos face similar challenges in finding and getting affordable housing like other racial and ethnic groups, but some nuances are particular to their experience.

Income, age, education, along with other factors specific to foreign-born Hispanics-Latinos like country of origin, citizenship status, and the number of years in the U.S. are factors that cannot be ignored in discussing solutions to housing disparities.

Programs addressing structural racism and economic disinvestment need to be inclusive of Hispanic-Latino families; specialized outreach is designed to bridge information gaps through education, counseling, and financial literacy courses that are culturally determined.

Housing is a Human Right was first published in The Chicago Reporter.

ILLatinoNews partners with The Chicago Reporter in best serving the Hispanic-Latino communities of Illinois.

Cover Photo by Andra C Taylor Jr on Unsplash