Publisher’s Note: Please participate in a short survey at the end of the story. Knowing how this story may have influenced you will help guide our future reporting...Thank you!

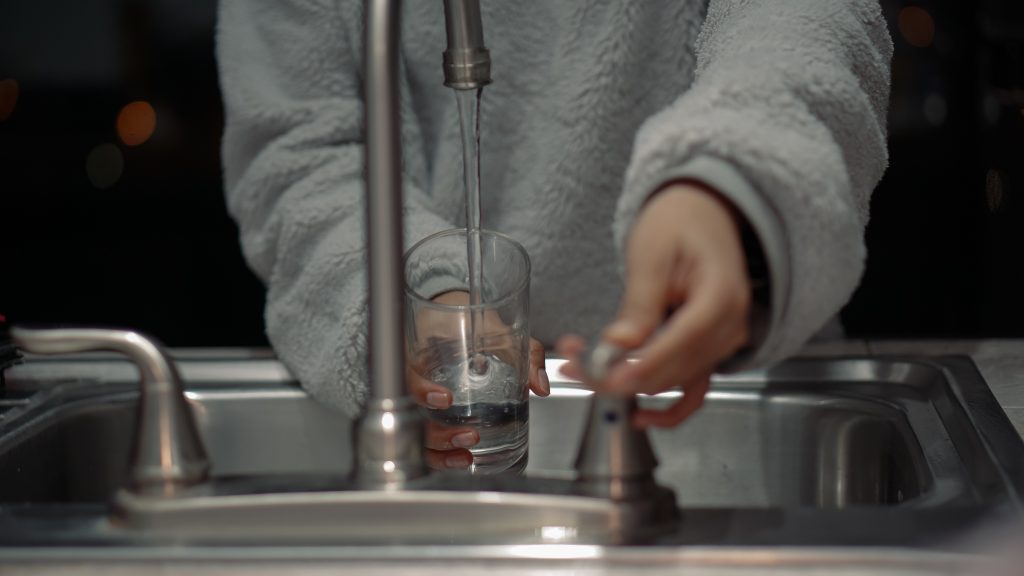

When Anthena Gore was a teenager, she noticed that water in her home tasted different than water at school or at her friends’ houses in the suburbs. She also noticed that other Black Chicagoans near her North Lawndale residence had a similar experience.

Gore, an adolescent at that time, felt drawn to the natural world, especially water – “the only digestible utility we have,” she said that is so simple yet essential. Years later, she turned her fascination into a profession and became a programs strategist at Elevate, a nonprofit organization designing programs to bring clean and affordable heat, power, and water to vulnerable communities.

Working with water, Gore still believes it is simple. “It’s really the system that we have built, the infrastructure we have used, and the way we have structured our communities that makes something so simple very difficult,” she says. And she knows about it first-hand too:

Gore is a co-author of City of Chicago Water Affordability Analysis, a joint report from Elevate and the Metropolitan Planning Council. According to the report, in Chicago, the water burden is not evenly distributed across households of different races or income levels.

The water bill burden is the percentage of a household’s income that goes toward paying water bills

“We saw that for Chicago’s lowest-income households, the burden is about 10%, “Gore explained. “Which is way over the 4.5% threshold that the Environmental Protection Agency set nationally.”

Translated into more straightforward language, low-income households in Chicago have to pay a disproportionally big chunk of their income for water. Big bills result in water debt or shutoffs, leaving families without water.

Which households are the most affected? Since the household-level income data is not available, Elevate looked at the census tract and the income quintiles – groups within the population that are compiled based on how much of their income they have left to spend freely after taxes and other deductions – to isolate small geographic regions and determine average household income in it.

The report found that the most affected households in Chicago are on the city’s West and South sides – Such as Austin and Humboldt Park on the West side and Riverdale and South Deering on the far Southside – where the majority of the population is non-White. For example, the water bill burden for Black households in places like Riverdale reaches an alarming 19 percent of the household’s total annual income. In contrast, the water bill burden for majorly White families, for example, on the North Side, sits at 4 percent. Oliver Ciciora, an environmental justice organizer with the Southsiders Organized for Unity and Liberation (SOUL), attributes the disproportion to environmental racism and historical redlining of the city.

Ciciora says investments in Black and Brown low-income communities are scarce – to the point where lack of such an essential service as transportation prevents Southsiders from accessing Downtown Chicago and its higher-paying job market. Gore agrees: “In certain places [across Illinois], the incomes have kept pace or outpaced the water expenses for households,” he says. “In many of Chicago’s southern suburbs, the incomes have not kept pace.”

How is water billed in Chicago?

To answer why water expenses are increasing in Chicago, it is vital to understand how billing works: Each water bill includes charges for the sewer and garbage lines, fees, and additional payments. The average bill increases drastically – by $500 annually – if a household is not metered. In this case, a home gets billed once every six months, while its metered counterpart receives bills every two or three months. With significant gaps, bills are more costly, resulting in higher taxes and more frequent penalties for late payment.

How is the City of Chicago responding?

The election campaign of now-Chicago’s-mayor Lori Lightfoot relied heavily on water-related promises. The promises came to life with varying success:

In 2019, when Lightfoot took office, around 150,000 households in the city had received shutoff orders. The same year, the mayor introduced a moratorium on water shutoffs, banning shutoffs due to non-payment. However, the pandemic prolonged the moratorium, which expired on April 1, 2022. By the end of April, the mayor re-introduced it, aiming to ban water shutoffs again, but it was voted down in May 2022. Water commissioner Andrea Cheng said at the time that the Chicago City Council generally agreed with the intent of improving water affordability. Still, it would also not be possible to implement what the ordinance required.

Anthena Gore says water advocates are pushing for permanent moratoriums on shutoffs.

In 2019 Chicago terminated the MeterSave Program –which had installed 130,000 meters citywide since its launch in 2009 – citing concerns with lead levels in the water. In May 2022, however, Major Lightfoot pledged to resume the voluntary installation of water meters to 180,000 households without them.

Oliver Ciciora is skeptical about the initiative: “The current ordinance about metering is not concrete,” he says. “It states that the City may change the meters within 90 days, but it doesn’t say that they will install a meter into your home.”

As the metering process might prove lengthy still, Gore suggests formulating a new calculation for nonmetered households. The current formula is based on factors like the square footage of the building, the number of outputs, and others, so “bills do not reflect the actual usage of water in the household,” Gore adds.

In 2020, Chicago also switched to a permanent utility billing relief program. Through the program, qualified residents of Chicago will be paying their water and sewer charges – with garbage charges not included – at a 50 percent reduced rate. In addition, after paying on time for 12 months, they will be forgiven their past water debt.

“[Residents] can stay on the program indefinitely as long as they are income-eligible,” Gore explains. “So that helped a little bit with the non-meter issue, but it doesn’t exactly address the entire affordability challenge across the city.” Indeed, the program is limited to homeowners of single-family or 2-unit properties whose income qualification is generally 200 percent of the federal poverty level.

Is there a better approach to water affordability?

Ciciora and his colleagues at SOUL have been working closely with their colleagues in Baltimore, Maryland, in an attempt to advocate for an equivalent of the city’s successful Water ForAll program.

In 2015 the city of Baltimore was facing a wave of water shutoffs, where 20 thousand households were left without access to water. Advocacy groups, such as Food and Water Watch, got involved and have since been trying to change the city’s approach to water. As a result, Baltimore passed the Water Accountability and Equity Act this year – the model SOUL hopes to implement in Chicago.

“The idea of this model is income-based water affordability,” explains Mary Grant, the Public Water for all campaign director at Food and Water Watch. The program uses a formula to calculate the maximum amount of bills a resident should pay for annual water and sewer services based on the household income percentage. The percentage can not exceed 3 percent of a household’s income and so would not burden it to the point where residents are forced to remain without water.

Where grassroots organizations first popularized the income-based approach two decades ago, Philadelphia was the first and only city before Baltimore to pass the law in 2017. Since then, “they gave about $10 million in discounts a year, but the net cost after you account for improved bill payment patterns is $2 million,” Grant says. “So they’re actually only collecting $2 million less, even despite providing $10 million in discounts.”

For Grant, this is evidence of improved bill payment patterns, where the city is collecting more money after assisting than it used to without it. “It’s a win-win situation for the city and the customers,” Grant adds.

Despite seemingly positive data from Philadelphia, cities have been reluctant to follow suit: In Detroit, advocates have fought for years, collecting data and generating research, but the city has not passed the law yet. Mary Grant sees this as a problem that easily translates to Chicago’s situation:

“The utility itself can be hesitant to change without good leadership, right?” She says. “You need proactive leadership and legislation to make that change.”

“It’s really the system that we have built, the infrastructure we have used, and the way we have structured our communities that makes something so simple very difficult”

Athena Gore, Strategist, Water Programs, Elevate

Gore sees cultural factors in Chicago’s unwillingness to change:

“The [utilities] industry has been predominantly homogeneous for half a century, with infrastructure that has not been upgraded for almost two centuries. America, in general, is at a turning point right now where once we bring everybody in, we can start from a place of justice.” She adds that affordability concerns should start with respect for every individual affected.

Mary Grant echoes her sentiment by concluding in a clear, digestible manner – isn’t water the only digestible utility after all? – “Just providing assistance isn’t enough. You really need to meet people where they’re at, making sure they have bills that are affordable for them based on their income.”

Cover Photo by SHTTEFAN on Unsplash

Irina Matchavariani is a graduate student at the Missouri School of Journalism.

She is working with Illinois Latino News (ILLN) as part of the Donald W. Reynolds Journalism Institute’s (RJI) Student Innovation Fellowships program, gaining hands-on experience helping the outlets connect with their audiences.

A native of the Republic of Georgia, Irina’s experience includes working with Vox Magazine and the Columbia Missourian.

Please take our short survey

This story is a collaboration between Illinois Latino News and the Chicago Reporter, partners in best serving our communities.