IL Latino News produces and amplifies stories focused on the responses to the social determinants of health. Social and Community Context is the connection between characteristics of the contexts within which people live, learn, work, and play, and their health and well-being. This includes topics like cohesion within a community, civic participation, discrimination, conditions in the workplace, and incarceration.

Yumary Briseño looked at her 12-year-old daughter. Her tender eyes gazing up at her, filled with worry.

“Mom, I’m hungry.”

Briseño gave her daughter the only food she had in her home—a few flour arepas and a can of tomato sauce.

“Mom, that’s not food.”

Holding back tears, Briseño realized it was time to flee Venezuela.

Briseño said she did not want to come to the United States, but with the rising economic crisis in her home country, she left in hopes to provide a better life for her daughter and mother.

Her restaurant business in Venezuela was declining and had no success finding another job that paid her enough to support her family.

“I had to do it,” she said.

Briseño’s journey to the United States was not easy. She saw women and men raped with her own eyes. She saw migrants being robbed and shot at. She encountered fear, hunger and fatigue.

She witnessed frustration grow among other migrants during her month-long travel, many of them picking fights with each other over water.

“If I could turn back time, I’d reconsider a million times about taking on the journey,” Briseño said.

Oftentimes, she went to sleep on the streets fearful that she would be killed.

“It’s an experience I don’t wish upon anyone,” she said.

Since late August, Republican Gov. Greg Abbott has bussed around 3,700 migrants to Chicago from the U.S. and Mexico border in Texas. At least 425 are school-aged children according to ChalkBeat. Most of the migrants are seeking asylum, yet some are unaware they have arrived in Chicago in the first place.

The influx of undocumented migrants is part of Abbott’s plan to send them to Democratic ‘sanctuary’ cities.

Abbott has openly criticized on social media the Biden administration’s attempt to lift Title 42, a federal act which authorizes denying asylum seekers in the U.S. during the Covid-19 pandemic prior to the shipment of migrants.

Despite her experiences, Briseño said she was one of the lucky ones.

Her journey led her to spend three days at the Migrant Resource Center in San Antonio, Texas where a woman at the center gave Briseño airplane tickets to Chicago.

When she arrived in the city, she met pastors Jacobita Cortes and Elvira who did not want to disclose her last name.

Elvira and Cortes turned the Adalberto Memorial United Methodist Church in Humboldt Park into a sanctuary for arriving migrants. They provide them with shelter, clothes, food and education on how to navigate public transportation.

Cortes said the church has received around 150 migrants. Their goal has been helping them find jobs, apartments, but most of all, help restore their faith and human rights.

During a church mass, Elvira told her experience as someone who was once undocumented to the newly arrived.

She turned her head, acknowledging the eyes of everyone in the small room and said, “Today, you all are arriving in paradise. But a paradise, why? Because others before us, even way before me, people fought so that in that time, I could have rights.”

Elvira was deported from the United States in 2007 and was not allowed to enter the country for twenty years. Despite her undocumented status, she would travel to the U.S. Mexico border and help people cross over.

There were moments she looked up at the sky and thought, “Lord but what am I doing here?”

Elvira said even though there were days she was filled with doubt and fear that she would be penalized again, she wanted to help people create a better life in the U.S.

“I wanted for no other mother and father to be separated from their children. For no other father and mother to be shamed. That no other worker be shamed for the simple act of wanting to work.”

She reminded the migrants that their path will not be an easy one but to continue fighting.

Cortes said she reminds them that despite their country’s crisis, they should not let go of their roots.

“Like I tell our Venezuelan brothers, never forget or feel embarrassed of your village, of your country,” Cortes said.

Cortes was also once a migrant herself, she came to the United States at 17-years-old from Michoacán, Mexico. She said it is now the duty of people who share similar migration experiences to help them.

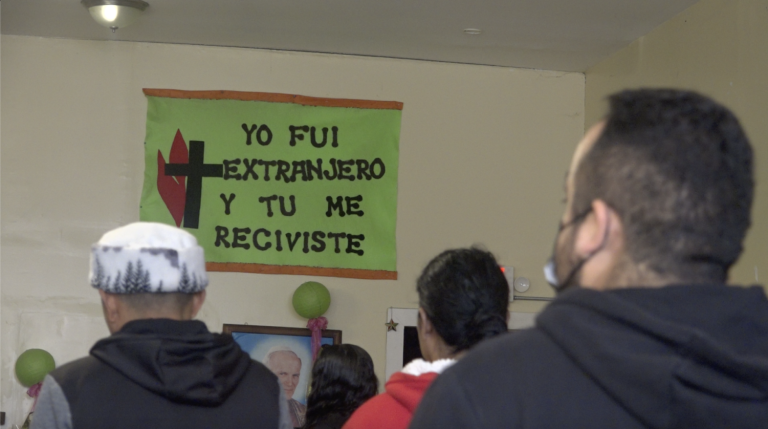

Her message transcents through the walls of the church with two green signs, one in Spanish and the other in English that read, “I was a stranger and you welcomed me.”

“Just as they arrived, they can have that heart to keep helping the rest. To not forget those who were left behind,” Cortes said.

Through similar migration experience or their own sense of calling, many Latinos across Chicago have found their own ways to help those seeking asylum.

Baltazar Enriquez, president of the Little Village Community Council (LVCC) was at Union Station on Aug. 31, the night the first bus of migrants arrived in Chicago.

He received a call from Univision cameraman Enrique García Fuentes, asking him if they could use the LVCC hall space to house the migrants. Although Enriquez agreed, he did not realize the ‘massive’ amounts of people that were seeking asylum.

LVCC volunteers quickly gathered supplies such as clothes, blankets, food and transportation. Enriquez called for help from city officials including Congressman Chuy Garcia, Illinois Latino Caucus Leader Aaron Ortiz and Cook County Commissioner Alma Anaya. Enrique said none of them answered his phone calls nor called him back at a later time.

“The city has helped us with nothing. The state has helped us with nothing. The county has helped us but nothing. The federal government has not helped us with anything.”

In October, Mayor Lightfoot gave $5 million for the city to support the incoming migrants, according to Bloomberg Magazine. However, the LVCC did not have any financial support from the city according to Enriquez.

Enriquez said the Little Village neighborhood always welcomes immigrants. As part of one of the city’s largest Mexican communities, he says they always, “lend a helping hand.”

Whether on the front lines or not, the mobilization of many Latinos across the city to support those arriving come in various forms.

Emily Vallejo, daughter of Peruvian immigrants and student at DePaul, started a clothing drive for migrants through the Latinx cultural group known as MESA.

She said her parents and grandparents immigration story has fueled her activism.

“It’s always kinda been a big part of why I felt like I need to do things is because I see my family in other people,” Vallejo said.

Vallejo said she wants to give back to her community such as the incoming migrants because her family paved the way for her to do so.

“I feel like it would almost be doing a disservice to my family if I weren’t saying this is messed up or we should be mobilizing.”

Vallejo said many of the older generation of Latinos focused on ‘surviving’ in the United States, rather than engaging in forms of activism.

These acts of survival were often sending money back to their families or simply ensuring there was food on the table.

As migrants continue to arrive, Briseño said all she wants is to be granted permission by the U.S. government to work. She wishes to provide for her family, especially her daughter.

“She is my strength to keep fighting.”

Publisher’s Notes: This story was written by DePaul University students, Stephania Rodriguez, Nadia Carolina Hernandez, and Jacqueline Cardenas.

Jacqueline is the editor-in-chief of La DePaulia, DePaul University’s Spanish language newspaper. She is a multimedia journalist and the event coordinator for the university’s National Association of Hispanic Journalists (NAHJ) student chapter. Jacqueline is a first-generation Mexican-American who aspires to diversify the broadcast news industry.

She is an Hortencia Zavala Foundation (HZF) fellow in the 2022 class, Journalism Camp: covering race, ethnicity, and culture.

You can read the Spanish language version of Chicago Latinos receive migrants with open arms by clicking on Latinos en Chicago reciben con brazos abiertos a migrantes después de un camino difícil.

Illinois Latino News (ILLN) and La DePaulia are partners in best serving the Hispanic-Latino community.